Understanding Your Brewing Water

Brewing water plays a very important role in the flavor of your homebrewed beer. Knowing the character of your local water source as well as how to adjust it to improve your beer is a critical skill, particularly for more advanced brewers.

Water impacts beer in three ways. Water ions are critical in the mashing process for all grain brewers, where the character of the water determines the efficiency and flavor of the extracted wort. Water also affects the perceived bitterness and hop utilization of finished beer. Finally, water adds flavor directly to the beer itself – as water is the largest single component in finished beer.

The effect of brewing water on beer can be characterized by six main water ions: Carbonate, Sodium, Chloride, Sulfate, Calcium and Magnesium.

Adjusting your WaterDifferent styles of beer require different water profiles. Often a particular beer is associated with the water profile of the city in which the beer originated. For a listing of water profiles for popular brewing cities of the world, you can visit our water profile listing. If you have a target profile in mind, you can adjust your water to match that profile.

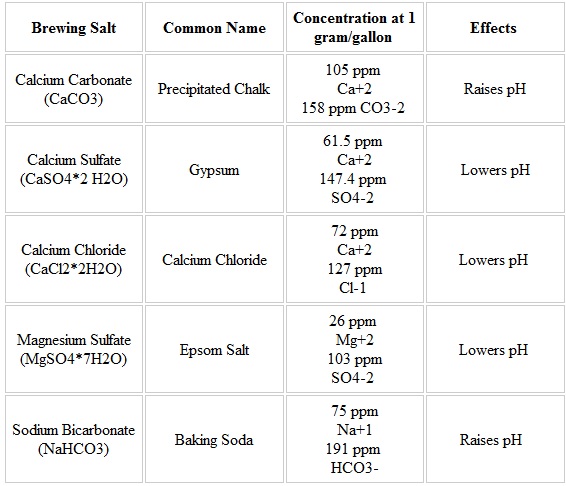

You can dilute your local tap water with distilled water if some ion counts are too high for your target water profile. Similarly you can use additives to increase the level of key ions. Popular additives include table salt (NaCl), Gypsum (CaSO4), Calcium Chloride (CaCl), Epsom Salts (MgSO4), Baking Soda (NaHCO3), and Chalk (CaCO3).

Unfortunately the additives do not add a straightforward amount of ions to the water profile, so its best to use some kind of water profile tool to adjust your local water supply to reach a target profile. Usually only a few grams of additives is required to achieve your target profile. BeerSmith has a water profile tool available to perform this very function. Other water profile tools are also available online.

Brewing Water Profiles

Brewing Water Profiles from Beersmith

Source water profiles from around the world on Brewer's Friend

Target Water Profiles on Brewer's Friend

You can get a water report from your local municipality that will contain the mineral content of your water supply. On a water report you will often see these listed as parts per million (ppm) which is equivalent to one milligram per liter (mg/l). Each of the critical ions is described below:

Carbonate and Bicarbonate (CO3 and HCO3)Carbonate is considered the most important ion for all grain brewing. Carbonate (or bicarbonate), expressed as “total alkalinity” on many water reports, is the ion that determines the acidity of the mash. It also is the primary determinant in the level of “temporary hardness” of the water. If carbonate levels are too low, the mash will be too acidic, especially when using darker malts (which have higher acidity). If carbonate is too high, mash efficiency will suffer. Recommended levels are 25-50 mg/l for pale beers and 100-300 mg/l for darker beers. Note that bicarbonates and temporary hardness can be reduced by pre-boiling the water – the precipitate that falls out after boiling is primarily bicarbonate.

Sodium (Na)Sodium contributes body and mouthfeel to the beer, but if used in excess will result in salty seawater flavors. High sodium water often comes from household water softeners, which is why most brewers recommend against mashing with softened water. Sodium levels in the 10-70 mg/l range are normal, and levels of up to 150 mg/l can enhance malty body and fullness, but levels above 200 mg/l are undesirable.

Chloride (Cl)Chloride, like sodium, also enhances the mouthfeel and complexity of the beer in low concentrations. Chlorine is often used in city water supplies to sanitize, and can also reach high concentrations from use of bleach as a brewing sanitizer. Heavily chlorinated water will result in mediciny or chlorine-like flavors that are undesirable in finished beer. Normal brewing levels should be below 150 mg/l and never exceed 200 mg/l. If you have heavily chlorinated city water you can reduce it using a carbon filter or by pre-boiling the water for 20-30 minutes before use.

Sulfate (SO4)Sulfate plays a major role in bringing out hop bitterness and adds a dry, sharp, hoppy profile to well hopped beers. It also plays a secondary role to lowering Ph of the mash, but the effect is much less than with carbonates as sulfate is only weakly alkaline. High levels of sulfate will create an astringent profile that is not desirable. Normal levels are 10-50 mg/l for pilsners and light beers and 30-70mg for most ales. Levels from 100-130 mg/l are used in Vienna and Dortmunder styles to enhance bitterness, and Burton on Trent pale ales use concentrations as high as 500 mg/l.

Calcium (Ca)Calcium is the primary ion determining the “permanent hardness” of the water. Calcium plays multiple roles in the brewing process including lowering the Ph during mashing, aiding in precipitation of proteins during the boil, enhancing beer stability and also acting as an important yeast nutrient. Calcium levels in the 100 mg/l range are highly desirable, and additives should be considered if your water profile has calcium levels below 50 mg/l. The range 50mg/l to 150 mg/l is preferred for brewing.

Magnesium (Mg)Magnesium is a critical yeast nutrient if used in small amounts. It also behaves as calcium in contributing to water hardness, but this is a secondary role. Levels in the 10-30 mg/l range are desirable, primarily to aid yeast. Levels above 30 mg/l will give a dry, astringent or sour bitter taste to the beer.

You can get a profile of your local water supply from your city or water company. Also, often the local brewing club has already collected local water profiles for you to examine. In the water report, look for the 6 critical items listed above. Also, be aware that many local water suppliers will frequently flush their system periodically (often in the Spring) with highly chlorinated water, which can give you some very strange brewing results if you are unaware of their schedule.

Water PH

Those who have moved beyond their first few all-grain batches, and are starting to perfect the art of mashing, mash pH really matters. Poor control of mash pH will lead to off flavors including astringency from excessive tannins. Even more important, beer brewed in the proper pH range will have a better overall flavor profile, be well rounded and taste better. The reason is that pH is critical to proper enzymatic action during the mash. If the pH is too far off, the sugar conversion in the mash will be affected as well as the fermentability and flavor of the wort and beer.

Most tap water sources are slightly alkaline (pH above 7). However the grains we use in brewing are slightly acidic, which helps drive down the pH of the mixture. When brewing light colored beers, however, the acidity of the grains is not sufficient to drive the mash pH down to the desired level, so often additives are required to adjust the pH. In contrast dark grains are more acidic, so we can often hit our target mash pH level for dark beers without further additives.

You need to keep the pH of the mash between 5.2 and 5.5 during the mash. While commercial brewers who brew a single beer over and over again can sometimes accurately predict their mash pH in advance, most home brewers do not have the detailed water or grain knowledge to do this. So in order to control your mash pH you need to measure the pH directly in the mash after you have mixed your water and grains.

Measuring and Controlling Mash pH

- Lactic Acid – An organic acid produced by bacteria. Many home brew stores sell it in liquid form that is about 88% by weight solution, though this does vary so please refer to the instructions on the package. It is added a little at a time until you reach your target pH. It generally mixes well with beer flavors in the small quantities needed to adjust a typical mash.

- Acid Malt – This is typically pilsner malt that has been acidified using lactic acid and contains about 3% acid by weight. Acid malt is primarily used in Germany to comply with strict purity laws (Reinheitsgebot) that prohibit additions other than malt, water, yeast and hops to beer.

- Phosphoric Acid – An inorganic acid widely used in soft drinks. It replaces bicarbonate with phosphate and increases the phosphate content of the wort.

- Hydrochloric and Sulfuric Acid – Used by many commercial brewers, these acids are usually not widely available to the public. These can be dangerous to handle (are both highly caustic) and are not recommended for use by home brewers, and also can create significant off flavors if misused. Also do not use the muriatic acid found in pool supply stores as it is not food great and should be avoided.

- Buffers such as “5.2 Stabilizer” – These salts lower the mash pH by reacting with phosphates brought in by the malt. They can raise the hardness of the mash water in the process, but they are a great “fire and forget” alternative since you can often add a pre-measured amount of buffer to the mash and achieve the desired range.

On balance, I prefer to either use lactic acid or 5.2 stabilizer for home brewing as both are readily available in home brew supply stores and easy to use on a small scale.